Federalism seems a natural approach for education reform, as it might for transportation policy reform. The great majority of commutes to and from work by road or rail are within state borders, so why not have state and local government administer or regulate most roads and rail?

Similarly, nearly all trips to and from schools are within state borders, so why not have states and local governments administer or regulate schools? Why would the federal government be involved in education issues that involve families in single communities within single states?

One plausible federal role would be to address injustice. Southern states prevented minority students from attending neighborhood schools which they reserved for white children. These were democratic policies, that is policies that at the time majorities and their elected representatives favored. So the federal government stepped in and mandated schools be integrated.

Are there similar state and local education injustices today that harm minority or low-income students and could or should be addressed by federal government policy?

One justice issue, or procedure, reform calls for restorative justice in schools. The Centre for Justice and Reconciliation (a Christian Organization) advocates restitution or restorative justice reforms for the criminal justice system:

Restorative justice repairs the harm caused by crime. When victims, offenders and community members meet to decide how to do that, the results can be transformational.

Similar restorative justice reforms are advocated for public schools. Critics point out that disciplinary actions in public schools impact minority students at higher levels than other students (see, for example, “Yes, Schools Do Discriminate Against Students Of Color — Reports,” (HuffPost, March 13, 2014). Restorative Justice in schools looks to address and repair this disparity.

“When Restorative Justice in Schools Works,” (The Atlantic, December 29, 2015), explains:

In traditional school-discipline programs, students face an escalating scale of punishments for infractions that can ultimately lead to expulsion. But there is now strong research that shows pulling students out of class as punishment can hurt their long-term academic prospects. What’s more, data shows that punishments are often unequal. Nationally, more black students are suspended than white students, for example.

As a result, alternative programs like restorative justice are gaining popularity in public schools from Maine to Oregon. Early adopters of the practice report dramatic declines in school-discipline problems, as well as improved climates on campuses and even gains in student achievement.

The article notes there has been some federal involvement:

In addition to the growing body of research supporting the benefits of alternative campus discipline programs, there is now federal pressure for districts to rethink their practices: schools may face sanctions if discipline policies are found to unfairly target minority students.

(Though this “federal pressure” might no longer be current administration policy.)

“Is Discipline Reform Really Helping Decrease School Violence?,” (The Atlantic, June 28, 2016), reports incidents of bullying in New York City schools, and is sceptical reforms have been effective:

Schools are also turning to social-reform programs such as those that embrace the restorative-justice model, an approach that emphasizes bringing together the perpetrators and victims of misconduct through meetings and discussions.

But a lack of hard data and conflicting views on safety measures make it difficult to assess whether school violence is in fact increasing—and whether those measures are actually effective. Some observers worry that the absence of concrete information and confusion over the amount of violence in schools are hindering efforts to reduce violence and bullying.

There are disagreements on how best to measure school violence (as with other violence), in part because not all incidents are reported to authorities, and because what counts as violence varies:

At the local level, statistics on school violence can vary depending on the source. Walden pointed to state statistics showing that the number of violent episodes in New York City schools rose 23 percent from the 2013-14 school year to the one that ended in June 2015. But the New York City school administration uses police data showing that crime in the city’s schools declined 29 percent from the 2011–12 school year to the 2014–15 year. Some observers have said that the state data does not make a distinction between minor disciplinary problems in schools and more serious acts of violence and bullying. Critics also emphasize that the state data isn’t verified.

Nationally schools are safer than they were twenty years ago, and according to this scholar, “schools are much safer than the communities around them”:

“In general, schools are far safer now than they were 20 years ago,” said Dewey Cornell, a clinical psychologist and education professor at the University of Virginia. “Every major study in recent years has shown that schools are much safer than the communities around them. Students are much more likely to be injured in restaurants than on school grounds.”

After citing data showing school violence and bullying are underreported, the article says:

While many school districts are embracing restorative justice, there’s little hard data to show the approach is effective in reducing violence. Anecdotal evidence suggests that restorative justice can reduce violence in schools through exercises like group discussions that build empathy among students, Gregory said, but she and other education researchers are quick to say that there have been few carefully designed studies to back up these claims.

So maybe the federal government could focus on funding more research on what works in addressing violence and bullying in public schools. An earlier post quoted a Brookings Institution study on the history of federal involvement in education:

For most of the nation’s history, Washington confined itself to collecting data on school systems and disseminating information on the progress of education. Until 1965, when the Elementary and Secondary Education Act was passed, federal support for K-12 education was minimal.

Collecting information about restorative justice as an alternative to zero-tolerance and school expulsions would seem worthy information to disseminate.

See also “An Effective but Exhausting Alternative to High-School Suspensions,” (New York Times Magazine, September 7 2016).

This 2014 neaToday article, “NEA and Partners Promote Restorative Justice in Schools,” begins:

Educators cannot stand by as tens of thousands of African-American, Latino, and other students get pushed out of school for minor disciplinary infractions, said NEA President Dennis Van Roekel, who on Friday helped release a new toolkit that aims to end the “school-to-prison pipeline” through the use of restorative policies and practices.

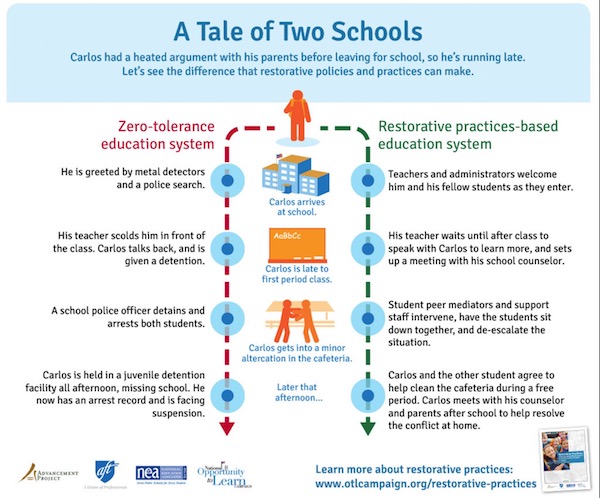

The article features this chart of alternative school justice systems: