Opposition to globalization has expanded and energized in the U.S. by both the Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump campaigns. “Globalization” sounds unappealing, like throwing goods and traditions from around the world in a blender and chopping them up. Consumers appreciate lower prices but worry about factories closing and “jobs being shipped overseas” to lower-paid workers in Mexico, China, Vietnam, or India.

Globalization, multilateral trade agreements, and “the international order” are regularly attacked by populists and nationalists in the US and Europe. And also in China.

China leadership has shifted nationalist in recent years, as discussed in “China Protection Writ Large,” (Wall Street Journal, January 31, 2017, online title “With Pen Plan, China Etches Nationalist Economic Policy“):

Studies rank China’s economy, the world’s second largest, among the most closed. From cars to wind turbines, Beijing limits foreign participation in domestic production. Citing “food safety,” Beijing insists that almost all grains consumed in China are domestically grown, and sets artificially high prices to support bumper harvests. State media touts locally made consumer products including bidets and rice cookers.

The WSJ story begins with a discussion of Chinese state initiatives to fund Chinese steel firms to produce higher-grade steel, such as needed for the tip or point in ballpoint pens. (The WSJ article offers a nice video overview telling the story.) China’s Ministry of Science and Technology funded this “meaningful breakthrough”:

The ministry provided $8.7 million for the research, which Beifa undertook with state-owned Taiyuan Iron & Steel Group Co., China’s largest stainless-steel mill. By September, the mill produced its first fully-domestic ballpoint pen.

Fortune also runs a story “China Couldn’t Make Its Own Ballpoint Pens—Until Now” (Jan. 10, 2017), noting Chinese firms produce 38 billion ballpoint pens each year but import ballpoint pen tips from Japan, at a cost of $17.3 million a year.

Premier Li Keqiang first drew the nation’s attention to the pen tip dilemma in January last year, lamenting that China still relied heavily on imported high-grade steel despite producing more than half of world’s crude iron and steel. State media reported that Li’s inability to make the tips reflected badly on Chinese manufacturing in general.

The article says Chinese firms spent “half a decade of research” to produce the pen tips. So here is a problem with politically-directed nationalist policies. Divide the $17.3 million a year pen tip “savings” over 38 billion pens. Chinese firms making tips themselves may reduce costs by some part of $0.000455 (about 1/20th of a penny per pen).

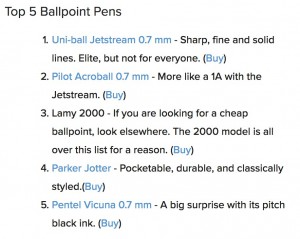

The Pen Addict reviews the top five ballpoint and other pens. The top rated ballpoint pens sell for $2.50 to $20 with $62 for the most expensive.

The Pen Addict reviews the top five ballpoint and other pens. The top rated ballpoint pens sell for $2.50 to $20 with $62 for the most expensive.

Probably there are better ways for Chinese ballpoint pen engineers to focus their attention than on that learning to make their own tips. A key challenge for Chinese firms is developing brands people worldwide will recognize and pay more for. But brand recognition usually follows innovation and marketing, not politically-directed manufacturing advances.

firms is developing brands people worldwide will recognize and pay more for. But brand recognition usually follows innovation and marketing, not politically-directed manufacturing advances.

“Why You Haven’t Heard of Any Chinese Brands” (The Atlantic, April 8, 2013) looks at the challenge China has faced developing brands:

Here’s a little thought exercise: Think of a Chinese brand. Any Chinese brand. Go on, I’ll wait. Give up? Don’t feel too bad: According to a recent poll conducted by HD Trade Services, 94 percent of Americans cannot think of a single brand from the world’s second-largest economy.

Strange, isn’t it? Japan and South Korea, countries China zoomed past in the GDP-rankings, boast globally-respected brands across a variety of industries. Even Sweden and Finland — mere minnows in comparison to China — offer IKEA and Nokia, respectively. Given China’s incredible transformation into an economic powerhouse over the past three decades, why doesn’t the country have more recognizable brands?

A key problem with nationalist policies follows from politicians supporting domestic “champions”– state-funded or subsidized firms state officials hope will succeed in the global economy. But governments have a poor track record choosing the best firms to support. Japan’s MITI tried for years to stop Honda from expanding from manufacturing motorcycles to cars, in part due to influence by successful and established Toyota and Nissan.

See also, China’s National Champions: The Evolution of a National Industrial Policy — Or a New Era of Economic Protectionism? (2013, pdf), which begins:

An increasing concern of foreign governments is the emerging pattern of industrial policies established by the government of the People’s Republic of China (PRC)…favoring Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) at the expense of their foreign counterparts.1 According to the US Chamber of Commerce, concerns that the Chinese government is retreating on opening its economy to foreign direct investment (FDI) are at a 10-year high among US companies directly investing in China (Reuters, 2010).2

Apart for the money governments spend directing research and development to area they deem strategic (ballpoint pens?), such subsidies and policies stoke nationalist responses in Japan, the U.S. and Europe:

While President Xi defends globalization abroad, his nationalist policies favor state-run companies back home. Many foreign companies and governments say China unfairly restricts access to its markets while flooding markets with low-price exports such as steel, helping to stoke a populist backlash abroad against globalization.

[Update: new Foreign Policy article, “Surprise Findings: China’s Youth Are Getting Less Nationalistic, Not More” (February 7, 2017):

For the United States’ part, its policymakers’ concern about a new crop of stridently anti-American Chinese youth may be overblown. If anything, future Chinese leaders may emerge from a generation noticeably less nationalistic than those that produced Xi and his predecessors.