Ending the Cuba trade embargo would shift sugar production back to Cuba and away from ecologically fragile lands in the U.S. “Protect the Everglades, not sugar farmers,” (Florida Sun Sentinel, Feb 16, 2017) argues:

Unfortunately, the most important state agency involved with Everglades restoration remains committed to the interests of sugar farmers instead of the environment.

At Wednesday’s hearing, South Florida Water Management Executive Director Peter Antonacci restated the district’s opposition to Negron’s proposal. Antonacci told senators that buying the land actually could hurt restoration efforts.

Why does the water management district oppose the idea? Because U.S. Sugar opposes the idea, and U.S. Sugar has donated $425,000 to Gov. Rick Scott’s political action committee since the 2014 election cycle. The company owns only a portion of one of the two parcels, but U.S. Sugar doesn’t want any more farmland out of production.

Sugar production causes political and pollution problems. Since the Cuban embargo blocked sugar imports, acreage around the Florida everglades put into sugar production increased four-fold.

U.S. sugar prices are far higher than market prices because of federal sugar quotas, raising costs for American consumers and reducing competitiveness of U.S. candy and chocolate companies.

In “Protectionist sugar policy cost Americans $3 billion in 2012,” AEI’s Mark Perry looks at costs and consequences of sugar trade restriction:

In “Protectionist sugar policy cost Americans $3 billion in 2012,” AEI’s Mark Perry looks at costs and consequences of sugar trade restriction:

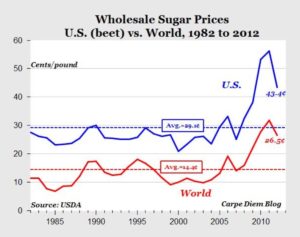

…American consumers and US sugar-using businesses, who have been forced to pay more than twice the world price of sugar on average since 1982 (29.1 cents for domestic sugar vs. 14.4 cents for world sugar…

See also Wall Street Journal: “U.S. Sugar Soars Above World Prices: Candy Makers Prepare Price Increases,” (WSJ, Dec 7 2014).

Apart from money costs to consumers are environmental costs from water diverted from and pollution seeping from sugar acreage into the Everglades ecosystem. According to colorful Grist article “Is sugar production still wrecking the Everglades?” (Grist, Jan 4, 2016).

As happens in so many places where agriculture butts up against nature, excess phosphorus in run-off contributes to algal blooms and otherwise mucks up the area’s ecological balance — in this case, feeding weedy plants like cattails and choking out native species like sawgrass. This kind of nutrient pollution can be traced back to several human sources, but a recent analysis by the nonprofit Everglades Foundation found that 76 percent of the phosphorus problem there comes from agriculture — and in that neck of the woods, that primarily means sugarcane.

The Everglades Foundation report (March, 2012) notes:

New Study: Agriculture Industry contributes 76% of the pollution in the Everglades, pays only 24% of the clean-up costs.

The EPA is suing the state of Florida for not reducing nutrient flows into Florida waters. Nutrient runoff into Florida waters is caused in part by four hundred thousands acres of sugar plantations in south Florida producing some thirteen million tons of sugar in 2011 (Agricultural Marketing Resource Center, May 2012).

Reducing pollution from Florida sugar plantations seems costly, as does reducing sugar production. But actually it is sugar production in Florida itself that is costly for American taxpayers and consumers. Turns out much less Florida sugar would be produced without diverse Federal sugar subsidies and import restrictions.

This March 13, 2013 WSJ article, “Big Sugar is Set for a Sweet Bailout” explains the latest chapter in the decades-long interventionist dynamics of the sugar industry (may be paywalled).

Interventionist dynamics means the ongoing political and economic consequences of government intervention in the economy. Government programs to support sugar producers may be designed to be modest efforts but they soon cause sugar production to go up, which pushes sugar prices lower, which hurts producers. So government looks to further legislation to fix the overproduction problem, but that causes later problems inspiring further legislation. Over the years layer upon layer of legislation makes sugar production ever more complex and convoluted, and tends to benefit established sugar producers while costing consumers and taxpayers millions or billions of dollars.

Some history of US/Cuba sugar can be found in “U.S Sugar Subsidies and the Caribbean’s Sugar Economies,” (Council on Hemispheric Affairs, July 31, 2013):

The U.S. government heavily subsidizes its sugar sector, imposes quotas on sugar imports, and then hectors developing countries on the wisdom of cutting back on their own subsidies. These measures protect private U.S. sugar producers from foreign competition, allowing them to seek unreasonably high prices in the U.S. market. U.S. consumers are likely to lose from these policies, as they end up paying higher prices at U.S. supermarkets, and, moreover, Caribbean sugar prices also have been adversely affected by U.S. protectionism in the sugar industry.

The article continues with some history:

The United States now has an absolute trade embargo with Cuba after U.S.-owned sugar companies in Cuba were nationalized in 1961. Before the revolution, 69.1 percent of Cuban trade overall and 54.8 percent of its sugar trade was with the United States. [2] The revolutionary government nationalized the sugar industry, a move that was seen as against free market principles. Yet Washington violates similar principles by keeping its sugar policy narrowly in place. Such double standards that block sugar imports from struggling Caribbean markets will continue to impair and distort U.S.-Caribbean relations.

However, opposing the Cuban government’s seizure of privately-owned sugar acreage and then blocking imports of sugar from seized acreage isn’t a “double standard.”

If the Canadian government seized a Ford engine plant in Windsor, Ontario, and then tried to continue exporting engines made there to the U.S., Ford motor company would file suit for return of their plant and for damages. And the U.S. government would support Ford (or maybe send in troops).

But revolutions happen around the world, and when the bullets stop flying and dust settles, lawyers and title insurance companies begin the work of negotiating and litigating to determine compensation and the return or property to owners.

The challenge of the Cuban revolution has been tied up in Cold War politics, and Florida politics. (See: “Why has the US embargo against Cuba lasted so long?” (The Telegraph, Dec 18, 2014) Cubans who fled Castro and prospered in the U.S. know the damage caused by the revolution then, and know from friends and relatives still in Cuba, the ongoing suffering and repression. Many believe opening trade for sugar imported from Cuban government lands would provide income to the communist government, helping sustain the ongoing repression of political dissidents and everyday Cubans.