China’s booming economy over the last decade has drawn vast quantities of agricultural goods and commodities like iron ore, coal, oil, and copper from around the world. Australia, Indonesia, and Africa are major sources of China’s agriculture and natural resource imports, and so is the United States and Latin America.

The Economist, in “Golden Opportunity: China’s president ventures into Donald Trump’s backyard,” (November 16, 2017) looks at China’s expanding economic integration with Latin American countries:

China’s aims in the region are expansive. In 2015 it signed a slew of agreements with Latin American countries promising to double bilateral trade to $500bn within ten years and to increase the total stock of investment between them from $85bn-100bn to $250bn. China also wants good relations in order to diversify its sources of energy, to find new markets for its infrastructure companies and to project power, both soft and military, in the western hemisphere.

The Economist further reports:

Four raw materials—copper, iron, oil and soyabeans—account for three-quarters of the region’s exports to China, a greater share than they do of trade with the rest of the world.

In “Mexico’s Revenge: By antagonizing the U.S.’s neighbor to the south, Donald Trump has made the classic bully’s error: He has underestimated his victim,” (The Atlantic, May, 2017), Franklin Foer, though skeptical of globalization in general, notes the benefits of increased trade and investment after NAFTA:

A generation after the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement, the United States and Mexico couldn’t be more interdependent. Anti-Americanism, once a staple of Mexican politics, has largely faded. The flow of migrants from Mexico to the U.S. has, more or less, abated. Economic ties have fostered greater intimacy between intelligence services and security agencies, which are today deeply enmeshed in each other’s business.

If the Trump Administration undermines US/Mexico trade and investment, the door for China/Mexico trade and investment opens wider. Foer notes China has invested less in Mexico than in other Latin American countries:

The Chinese invested heavily in places like Peru, Brazil, and Venezuela, discreetly flexing soft power as they funded new roads, refineries, and railways. From 2000 to 2013, China’s bilateral trade with Latin America increased by 2,300 percent, according to one calculation. A raft of recently inked deals forms the architecture for China to double its annual trade with the region, to $500 billion, by the middle of the next decade. Mexico, however, has remained a grand exception to this grand strategy.

Here is Atlas Media interactive graphic of China’s $1.2 trillion dollars of 2015 imports from around the world:

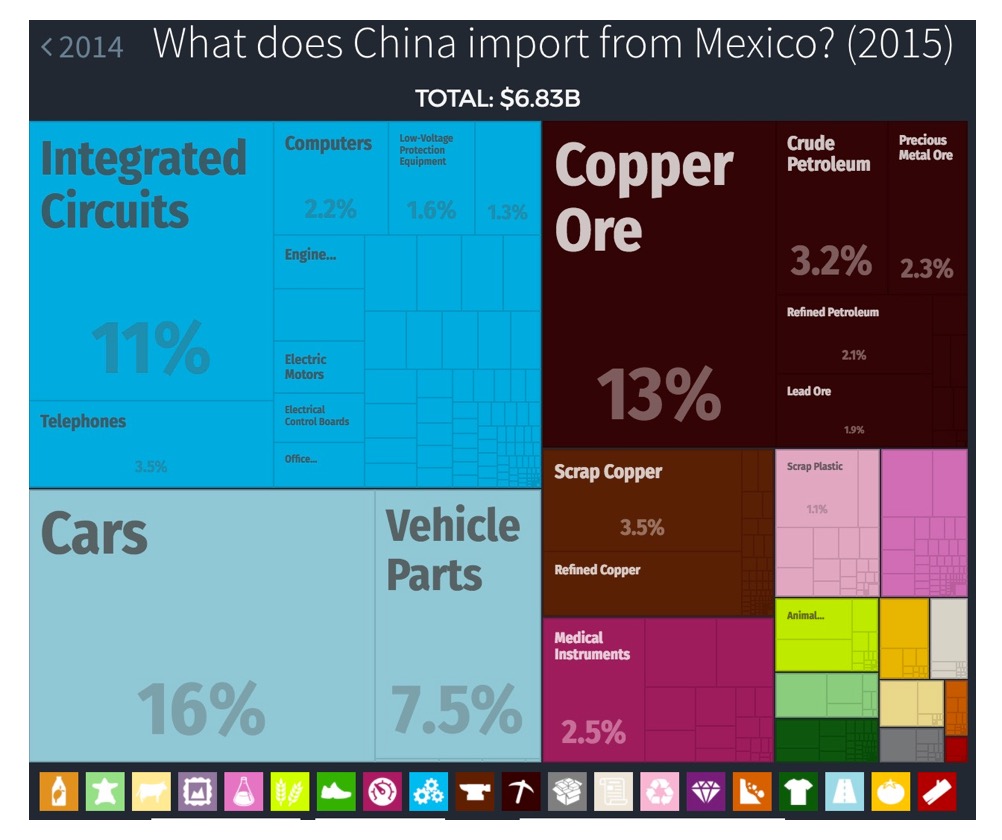

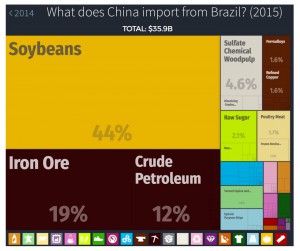

The Atlas Media page allows selecting China’s imports by country as well as year. Brazil and Mexico are by far the largest economies in La tin America (Argentina and Columbia are next largest), so not surprisingly Brazil and Mexico export the most to China each year. At right is visualization of 2015 Chinese imports from Brazil, valued at nearly $36 billion.

tin America (Argentina and Columbia are next largest), so not surprisingly Brazil and Mexico export the most to China each year. At right is visualization of 2015 Chinese imports from Brazil, valued at nearly $36 billion.

Next visualization (below right) is of 2015 Chinese imports from Mexico, valued at almost $7 billion. China is currently importing less than one-fifth as much from Mexico as from Brazil. Brazil’s economy is larger, but not that much larger.

As with China, India, Indonesia, Southeast Asia, and much of Africa, Latin Americans have prospered over the last decade. Mexico’s economy didn’t match Brazil’s expansion until the last few years when political scandals disrupted Brazil, and Mexico got on track. “Can Mexico reclaim its title as Latin America’s economic powerhouse?,” (Global Risks Insight, February 26, 2016), reports:

As with China, India, Indonesia, Southeast Asia, and much of Africa, Latin Americans have prospered over the last decade. Mexico’s economy didn’t match Brazil’s expansion until the last few years when political scandals disrupted Brazil, and Mexico got on track. “Can Mexico reclaim its title as Latin America’s economic powerhouse?,” (Global Risks Insight, February 26, 2016), reports:

In fact, in the decade to 2012, the region as a whole averaged growth of 4.1 percent, while Mexico’s economy grew at a rate of 3.3 percent. During this boom, Latin America experienced an economic transformation with laudable achievements: More than 70 million were lifted out of poverty while the middle class expanded by more than 50 percent.

Yet these developments were not echoed in Mexico, where the poverty rate stagnated. Even today, over 46 percent of the population live in poverty, with a third of Latin America’s extreme poor in Mexico.

China imports raw materials from Latin American countries, but also invests heavily in factories and infrastructure. After decades of rapid economic development, Chinese firms have developed expertise in both industry and infrastructure.

“Mexico’s Revenge” argues the Trump Administration’s hostility to Mexico will encourage Mexico to agree to much more Chinese industry and infrastructure investment:

Until recently, a Mexican–Chinese rapprochement would have been unthinkable. Mexico has long steered clear of China, greeting even limited Chinese interest in the country with wariness. It rightly considered China its primary competition for American consumers. Immediately after nafta went into effect in 1994, the Mexican economy enjoyed a boom in trade and investment. …

Chinese economic and military relations with Mexico have expanded in recent months:

In October, China’s state-run media promised that the two countries “would elevate military ties to [a] new high” and described the possibility of joint operations, training, and logistical support. A month and a half later, Mexico sold a Chinese oil company access to two massive patches of deepwater oil fields in the Gulf of Mexico. And in February, the billionaire Carlos Slim, a near-perfect barometer of the Mexican business elite’s mood, partnered with Anhui Jianghuai Automobile to produce SUVs in Hidalgo, a deal that will ultimately result in the production of 40,000 vehicles a year.

A further note on national security concerns is touched on in The Atlantic article, which says US and Mexican security agencies work together:

Mexico was a primary subject for incendiary right-wing news accounts. During the Obama years, conservative media in the U.S. blared unsubstantiated stories about Islamic State operatives camping out in Ciudad Juárez, waiting to commit car bombings across the border. It was reported on Fox News that copies of the Koran had been strewn along smuggling routes into Texas…

In “Terrorism in Latin America (Part One): The Infiltration of Islamic Extremists,” (NCPA Issue Brief No. 206, March 2017), David Grantham looks at the history of Islamic extremism in Latin American countries, and recommends the Trump Administration:

In “Terrorism in Latin America (Part One): The Infiltration of Islamic Extremists,” (NCPA Issue Brief No. 206, March 2017), David Grantham looks at the history of Islamic extremism in Latin American countries, and recommends the Trump Administration:

…shift U.S. priorities in Latin America to strategies that preemptively disrupt the financial networks of Islamists, aid allied governments with legal and law enforcement support, and increase intelligence-gathering capabilities in the region.

Leverage for security cooperation often follows from economic engagement. If U.S. trade and investment policy shifts to disengage from Mexico and other Latin American countries, consequences include expanding Chinese economic integration and military cooperation as well as reducing joint U.S./Latin American cooperation on security and intelligence concerns.