The Chinese government has strong incentives to advance environmental goals, from reducing air and water pollution to restoring habitat and ecosystems. “Trees or Shrubs? Study Disputes Success of China’s $100 Billion Forest Effort,” (New York Times, May 3, 2017) challenges UN and Chinese government forest planting claims of: “167,568 square miles of forest, an area slightly larger than California”:

But the newly released study, based partly on an analysis of high-resolution photographs, found that China had gained only about 12,741 square miles of forest over the same period, an area roughly the size of Maryland. And it found that much of the government’s reported new forests were actually just collections of shrubs.

The study’s:

findings were consistent with recent research suggesting that China’s forest resources have not significantly increased despite the government’s extensive tree-planting campaign or its efforts to halt commercial logging in forests.

The article notes there are some 800 different definitions for forest, so much room for confusion in trying to measure forest cover changes.

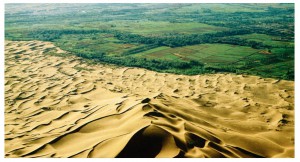

A 2014 Economist article “Great Green Wall,” (August 23, 2014) reports on China’s diminished forests and grasslands releasing sand to Chinese cities:

Blown from northern deserts and degraded drylands, it coats roads, clogs railways and desiccates pastures. According to Greenpeace, just 2% of China’s original forests are intact. Decades of rampant logging and overgrazing have speeded the degradation of its land and soil; over a quarter of its territory is now covered in sand.

(Maybe all this sand can help address another problem noted by the New York Times: “The World’s Disappearing Sand,” (June 23, 2016), and The New Yorker, “The World is Running Out of Sand,” (May 29, 2017)).

The Economist article notes forest planting projects have gone wrong:

Just 15% of trees planted on China’s drylands since 1949 survive today, estimates Cao Shixiong of Beijing Forestry University. Many died of age, as those grown from cuttings (as most are) only have a lifespan of around four decades. But many were simply unsuited to the soil. Monocultures are prone to disease. In Ningxia, in northwest China, a pest wiped out 1 billion poplar trees in 2000—two decades of planting efforts. In arid areas trees may even aggravate desertification by depleting groundwater and killing grasses that bind the soil.

Economists are not surprised that government forest plans failed since most other centrally-planned industrial and agricultural plans failed as well.

Similar mega-forest plans have failed in Africa, though with some emerging successes. The “Great Green Wall” Didn’t Stop Desertification, but it Evolved Into Something That Might, (The Smithsonian, August 23, 2016) tells of the plan was to plant a forest from Africa’s west to east to stop expanding deserts.

It was a simple plan to combat a complex problem. The plan: plant a Great Green Wall of trees 10 miles wide and 4,350 miles long, bisecting a dozen countries from Senegal in the west to Djibouti in the east. The problem: the creeping desertification across Africa. …

“If all the trees that had been planted in the Sahara since the early 1980s had survived, it would look like Amazonia,” adds Chris Reij, a sustainable land management specialist and senior fellow at the World Resources Institute who has been working in Africa since 1978. “Essentially 80 percent or more of planted trees have died.”

But while the top-down plans to create forests along the edge of African deserts failed, researchers found local farmers are expanding forest and productive agricultural land on their own:

Over two years traveling through Burkina Faso and Niger, they uncovered a remarkable metamorphosis. Hundreds of thousands of farmers had embraced ingenious modifications of traditional agriculture practices, transforming large swaths into productive land, improving food and fuel production for about 3 million people.

“This regreening went on under our radar, everyone’s radar, because we weren’t using detailed enough satellite imagery. We were looking at general land use patterns, but we couldn’t see the trees,” Tappan says. “When we began to do aerial photography and field surveys, then we realized, boy, there is something very, very special going on here. These landscapes are really being transformed.”

Innovative farmers in Burkina Faso had adapted years earlier by necessity. They built zai, a grid of deep planting pits across rock-hard plots of land that enhanced water infiltration and retention during dry periods. They built stone barriers around fields to contain runoff and increase infiltration from rain.

In Niger, Reij and Tappan discovered what has become a central part of the new Great Green Wall campaign: farmer-managed natural regeneration, a middle ground between clearing the land and letting it go wild.

Colonialism played a key role here, as colonial powers disrupted long-standing property rights institutions:

Farmers in the Sahel had learned from French colonists to clear land for agriculture and keep crops separate from trees. Under French colonial law and new laws that countries adopted after independence, any trees on a farmer’s property belonged to the government. Farmers who cut down a tree for fuel would be threatened with jail. The idea was to preserve forests; it had the opposite effect.

“This was a terrific negative incentive to have a tree,” Garrity says, during an interview from his Nairobi office. “For years and years, tree populations were declining.”

Unfortunately, colonial tree policies were kept in place after independence, and continued to damage natural ecosystems:

But over decades without the shelter of trees, the topsoil dried up and blew away. Rainfall ran off instead of soaking into cropland. When Reij arrived in Africa, crop yields were less than 400 pounds per acre (compared to 5,600 pounds per acre in the United States) and water levels in wells were dropping by three feet per year.

Since the 1980s local farmers have been restoring trees and, for example: aerial images show: “Niger’s Zinder Valley had 50 times more trees than it did in 1975.”

Africa’s green wall lessons can apply in China. Local farmers and land owners have strong incentives to discover ways to maintain and restore grasslands and forests.

A Michigan State University article claims: “China’s Efforts to Restore Forests are Working,” (MSU Today, March 18, 2016):

The MSU scientists examined the big-picture view of NASA’s Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer annual Vegetation Continuous Fields tree cover product, along with high spatial resolution imagery available in Google Earth. Then they combined data at different scales to correlate the status of the forests with the implementation of China’s program.

And, as the Chinese government has contended, the initiative is working and forests are recovering, with about 1.6 percent, or nearly 61,000 square miles, of China’s territory seeing a significant gain in tree cover. In comparison, 0.38 percent, or 14,400 square miles, experienced significant loss.

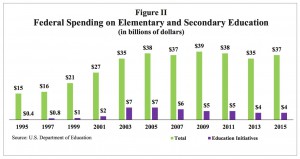

The claimed forest gain here is five times that cited in the first article above. A Stanford News article “China’s environmental conservation efforts are making a positive impact, Stanford scientists say,” (June 16, 2016), also claims positive results:

By 2000, China developed the Natural Forest Conservation Program and the Sloping Land Conversion Program, $50 billion projects aimed at reducing natural disaster risks by restoring forest and grassland, while also improving life conditions for 120 million poverty-stricken farmers.

However, this seems more a report on the intentions of the Chinese government than a report on actual progress. (More details in the article.)

The problem with economic planning…

At the center of economics are two sets of challenges: knowledge problems and incentives problems. The Chinese government recognized significant environmental problems caused by deforestation:

Officials in China began considering significant environmental reform following a series of natural disasters in the late 1990s that were exacerbated by human activities. In particular, in 1998, massive deforestation and erosion contributed to devastating flooding along the Yangtze River. Thousands of people were killed, and more than 13 million people were left homeless following $36 billion in property damage. (Stanford News)

But recognizing problems is a far cry from solving them. Central plans face challenges, even when they can pour $100 billion into planting trees. What trees and where? Who will water the trees?

Economist Lester Thurow, in a 1986 New York Times book review, observed:

Government ownership of all the means of production fails because it cannot answer a simple question: Who should stay up all night with a sick cow? In capitalism the answer is clear: the owner. In socialism the answer is not clear, and too often it is: no one.

Market economies with property rights and rule of law make clear who owns cows, cars, farmland, and trees. Across the U.S., privately-owned, state-owned, and federally-owned forests are managed differently. “Divided Lands: State vs. Federal Management in the West,” (March 3, 2015) contrasts state management where forest revenue often supports public schools, with federal forests. Alston Chase’s classic Playing God at Yellowstone focuses on incentives and park management challenges. Forest management benefits from market-generated information as well as property ownership-generated incentives.

From Incentive Problems to Information Problems…

The division of labor and expanding scope of trade allow people and companies to gain specialized knowledge and skills to better produce goods and services. In modern society, we benefit each day from a wide range of goods that we would have no idea how to produce.

For example, we benefit the mobility cars provide without knowing how to build or repair them (and benefit from trains, buses, Uber, and Lyft, even if we don’t know how to drive). We consume a wide range of foods without knowing how to farm or even much about cooking. People and firms that have this knowhow can be nearby or far away, which allows us to focus on producing other goods and services.

The knowledge problem follows from no single person or group having enough knowledge to produce all the goods and service they consume each day, week, or month. The “I, Pencil” story explains that no one in the world even knows how to make a pencil all the way from tree to writing.

Here are three “I, Pencil” YouTube videos: One, Two, Three, and an NPR story/segment: “Trace The Remarkable History Of The Humble Pencil” (plus “I, Smartphone” video from 2012).

F.A. Hayek’s famous journal article “The Use of Knowledge in Society,” (American Economics Review, 1945) takes a deeper look at how knowledge is divided around the world through international trade, mobilized by markets, with production coordinated by prices. Hayek offers the example of a copper ore mine flooded in Chile. Through the weeks after, reduced supplies of copper ore force copper refineries to scramble for other supplies, bidding up ore prices and encouraging other mines to expand production (usually with higher costs).

Copper refiners dealing with these higher prices in turn raise their prices, so companies producing pots, pans, jumper cables with copper search for substitutes, and raise their prices to consumers. Next, millions of consumers find higher prices for copper pans in Target, Walmart, and higher prices for copper jumper cables at Autozone. Higher prices signal some consumer to buy substitute goods (aluminum pans or jumper cables), or to put off buying until later.

Copper consumers have no knowledge of the flood reducing copper ore mining in Chile, but signals from higher prices encourage reduced of copper consumption by consumers as well as increased copper ore mining by producers. And higher prices boosts copper recycling (and, unfortunately, encourages thieves to steal even more copper wires (“Copper theft ‘like an epidemic’ sweeping US,” CNBC.com, July 30, 2013)

Markets and changing prices are sending millions of signals each day about shifts in the supply and demand of goods and services. Forests in China and the United States would benefit from better legal institutions and incentives to maintain and expand ecosystems. “China’s Reforestation Programs: Big Success or Just an Illusion?,” (YaleEnvironment360, January 17, 2012), looks at the debate of China’s efforts multi-decade reforestation effort:

…informally called the “Great Green Wall” — was designed to eventually plant nearly 90 million acres of new forest in a band stretching 2,800 miles across northern China.

That could make it the largest ecological restoration project ever accomplished. But some scientists who have examined long-term trends suggest this large-scale tree-planting campaign is far less than the miracle it appears to be. Indeed, Jiang Gaoming, an ecologist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, has characterized it as more of a “fairy tale.”

To be sure, trees have been planted, with millions of seeds dropped from airplanes and millions more small seedlings manually planted. But in an extensive analysis of such “afforestation” efforts published last year in Earth Science Reviews, Beijing Forestry University scientist Shixiong Cao and five co-authors say that on-the-ground surveys have shown that, over time, as many as 85 percent of the plantings fail.

Overview article: “China is building a Great Green Wall of trees to stop desertification,” (Plaid Zebra, February 16, 2016):

Overview article: “China is building a Great Green Wall of trees to stop desertification,” (Plaid Zebra, February 16, 2016):

In an effort to combat the loss of its grassland to the Gobi Desert, the Chinese Government started the Three-North Shelterbelt Project, also known as the Great Green Wall in 1978.

Overview article: “

Overview article: “ The above quote is from beginning of newsletter, this

The above quote is from beginning of newsletter, this

Consider the compelling movie of rural China,

Consider the compelling movie of rural China,  author has led his hero, step by step, from vagabondage to a position of respectability; and, in so doing, has incurred the charge, in some quarters, of exaggeration. It can easily be shown, however, that he has fallen short of the truth, rather than exceeded it. In proof, the following extract from an article in a New York daily paper is submitted:— “As a class, the newsboys of New York are worthy of more than common attention. The requirements of the trade naturally tend to develop activity both of mind and body, and, in looking over some historical facts, we find that many of our most conspicuous public men have commenced their careers as newsboys. Many of the principal offices of our city government and our chief police courts testify to the truth of this assertion. From the West we learn that many of the most enterprising journalists spring from the same stock.”

author has led his hero, step by step, from vagabondage to a position of respectability; and, in so doing, has incurred the charge, in some quarters, of exaggeration. It can easily be shown, however, that he has fallen short of the truth, rather than exceeded it. In proof, the following extract from an article in a New York daily paper is submitted:— “As a class, the newsboys of New York are worthy of more than common attention. The requirements of the trade naturally tend to develop activity both of mind and body, and, in looking over some historical facts, we find that many of our most conspicuous public men have commenced their careers as newsboys. Many of the principal offices of our city government and our chief police courts testify to the truth of this assertion. From the West we learn that many of the most enterprising journalists spring from the same stock.”