Economists Tyler Cowen & Noah Smith at Bloomberg are “Debating Free Trade and the Populist Backlash” (November 1, 2016 1:16 PM EDT).

For NSDA (and NCFCA) debaters, the benefits, costs, and pushback on U.S./China trade is at the center of economic and diplomatic relations with China. Alan Reynolds in the Wall Street Journal “What the China Trade Warriors Get Wrong” (Oct. 26, 2016 7:21 p.m. ET) says Trump advisor Peter Navarro is wrong in claiming the “U.S. and Europe in particular got the short end of that stick” after China joined the WTO in 2001:

… China joining the WTO had zero effect on U.S. tariffs against Chinese imports. But it did force China to cut weighted-average tariffs to 19.8% in 1996, down from 32.2% in 1992, according to World Bank estimates. They shrunk further to 14.6% in 2000 and 3.2% by 2014. Yet U.S. tariffs remained unchanged by China’s entry into WTO, staying between 2% and 3% on a weighted average.

Reynolds notes however, that joining the WTO did have a big short-term impact in China:

They found that China’s “aggressive restructuring led to the layoffs of 45 million workers between 1995 and 2002, including 36 million from the state sector.” If China’s entrance to the WTO was about “stealing jobs,” it certainly got off to a bad start. Even in the world’s most populous country, those tens of millions of lost jobs had a big effect.

Did U.S. imports surge after China joined the WTO? Reynolds quotes a recent front-page WSJ story: “Imports from China as a percentage of U.S. economic output doubled within four years of China joining the World Trade Organization in 2001. . . . By last year, imports from China equaled 2.7% of U.S. gross domestic product.” (How the China Shock, Deep and Swift, Spurred the Rise of Trump). But Reynolds says this is misleading and instead U.S. exports to China surged:

Those numbers might appear to suggest U.S. imports surged after 2001, but it was actually Chinese imports that exploded. China’s global imports jumped to 29.2% of GDP in 2005, according to the World Bank, up from 18.3% in 2001. Meantime, U.S. exports of goods to China quickly rose from $19.2 billion in 2001 to $69.7 billion in 2008, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis. With services added, the U.S. exported $169.2 billion worth of goods and services to China by 2014.

U.S. imports were 15.5% of GDP in 2005 and the main shift was reduced imports from Japan as imports from China rose:

A decade later, U.S. imports were still 15.5% of GDP—the same as 2005. The fact that China’s share of U.S. imports was up and Japan’s down did not mean the U.S. was importing more.

Japan shifted manufacturing to mainland China, building factories and training Chinese workers. So more goods flowed to the U.S. from these factories as imports of goods decreased from Japan.

Since 1990, media and special interest fears of Asian imports shifted from Japanese factories to Chinese factories. Consider this 1990 New York Times story: “Japanese Still Fear Trade Tensions With U.S.” (April 28, 1990):

Indeed, although American exports to Japan have risen in recent years, American imports – particularly automobiles, consumer electronics and machinery – have risen twice as fast.

Japanese officials say they feel lingering bitterness at the way they had to negotiate with the United States under the threat of sanctions, a principal tool of the Super 301 clause.

Japan viewed the Super 301 action as coercive, unilateral and illegal. Mrs. Hills was understood to have been advised by many American negotiators not to use it again this year.

Back to the present, this New York Times and Seattle Times article looks at overall international trade: “A little-noticed fact about trade: It’s no longer rising” (Originally published October 30, 2016 at 3:47 pm Updated October 30, 2016 at 7:41 pm) Global trade is flat and:

The United States is no exception to the broader trend. The total value of U.S. imports and exports fell more than $200 billion last year. Through the first nine months of 2016, trade fell an additional $470 billion.

For all the complaints about “free trade” by U.S. and E.U. politicians and industry associations, many new trade barriers are being thrown up by U.S. and E.U. governments:

Meanwhile, new barriers are rising. Britain is leaving the European Union. The WTO said in July its members had put in place more than 2,100 new restrictions on trade since 2008.

One example is a new Iron Curtain lobbied for by U.S. steel manufacturers. See “U.S. Imposes 266% Duty on Some Chinese Steel Imports” (March 1, 2016 7:23 p.m. ET), and “U.S. Steel Tariffs Create a Double-Edged Sword” which notes:

New tariffs on imports are boosting steel prices in the U.S., offering a lifeline to beleaguered American steelmakers but raising costs for manufacturers of goods ranging from oil pipes to factory equipment to cars.

So how much of the global slowdown in trade is due to falling construction and commodity prices, and how much is due to new U.S. and E.U. trade restrictions?

Binyamin Appelbaum’s NYT/Seattle Times article also claims:

The benefits of globalization have accrued

disproportionately to the wealthy, while the costs have fallen on displaced workers, and governments have failed to ease their pain.

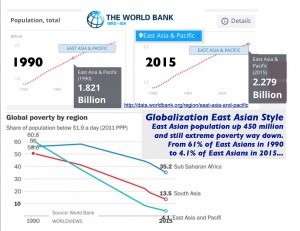

Appelbaum claim certainly doesn’t apply to everyday people in China and other East Asian countries. According to the World Bank “benefits of globalization” (international trade and investment) shifted billions out of extreme poverty.

East Asia’s population grew from 1.821 billion in 1990 to 2.279 billion by 2015, yet the percentage of East Asians in extreme poverty (earning less than $1.9 a day) fell from 60.8% of the population in 1990 down to 4.1% by 2015.

Maybe he just wanted to focus instead on the hundreds of East Asian business leaders now billionaires, and the tens of thousands millionaires.

Inequality of income increased as economic and political entrepreneurs built tens of thousands of enterprises from small to large, and some to very, very large. We could research further the income gains Chinese workers enjoyed over the last 25 years vs. gains to Chinese and foreign company founders and stockholders. Still, everyday people saw stunning gains in income and living standards thanks to relatively open trade with the U.S., E.U., and the rest of the world.

East Asian gains are discussed here too: “In 1990, more than 60% of people in East Asia were in extreme poverty. Now only 3.5% are.” (Vox Oct 2, 2016, 4:00pm)

It’s hard to overstate how astonishing and rapid the decline in extreme poverty in the past couple of decades has been. In 1990, more than a third of people on Earth lived on less than $1.90 a day, adjusted for local prices (this is the line the World Bank uses as its main metric). By 2013, barely 10 percent of people did; the rate had been cut by more than two-thirds. That’s one of the biggest and fastest improvements in human well-being in the history of the planet.

Appelbaum is maybe thinking more about how globalization impacts low and middle income American:

During the 1990s, global trade grew more than twice as fast as the economy. Europe united. China became a factory town. Tariffs came down. Transportation costs plummeted. It was the Wal-Mart Era.

Wal-Mart is of course a store where millions of low and middle income Americans have purchased billions of dollars worth of clothes, gadgets, and other goods made by Chinese workers. Did buying these goods hurt or benefit American consumers? Did purchasing less expensive goods from China hurt American manufacturers, “hollowing out” America’s middle class? (An earlier post noted the 40% gain in U.S. manufacturing output since 2000, and research showing most job losses were from automation.)

Well, this is an overlong post already. But, in addition to the Cowen/Smith above, here are a additional responses to populist “Death by China” claims. Bryan Riley of the Heritage Foundation’s argues “Trade With China Is a Net Plus for Americans” (August 31, 2016). This Cato Institute Commentary “The Truth about Trade” (April 11, 2016) adds more support for the gains from trade.

For a more in-depth discussion, see Dartmouth economist Doug Irwin’s “The Truth About Trade:What Critics Get Wrong About the Global Economy” in the July/August issue of Foreign Affairs,